Menstrual health concerns -

Products like rags, paper towels, and reused pads put menstruators at a heightened risk for urogenital infections, such as urinary tract infections and bacterial vaginosis 2. These products are also associated with outcomes such a skin irritation, vaginal itching, and white or green discharge 3.

Further, the emotional toll accompanying lack of access is related to poor mental health outcomes, such as elevated anxiety, depression, and distress scores 4.

It is essential that when we talk about period poverty, we keep in mind that not all menstruators are women, and not all women menstruate.

The reason this public health crisis is yet to be addressed is largely due to stigma. Stigma associates menstruation with uncleanliness and disgust instead of recognizing it as biologically healthy and normal.

The shame associated with periods prevents people from talking about it, which in turn averts dialogues about access to products, the tampon tax, and even the ingredients in our pads and tampons. Shame also surrounds the experience of menstruating as a trans person.

Coalitions of advocates each making even the smallest of ripples in their daily lives has the potential to give rise to seismic change. For the menstrual movement, this change is non-negotiable. We believe that menstrual equity can only be achieved when period products are accessible, safe, and destigmatized.

We also believe that this is attainable. Together, we will change the cycle. Ashley Rapp is a second year MPH student in the Epidemiology Department at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

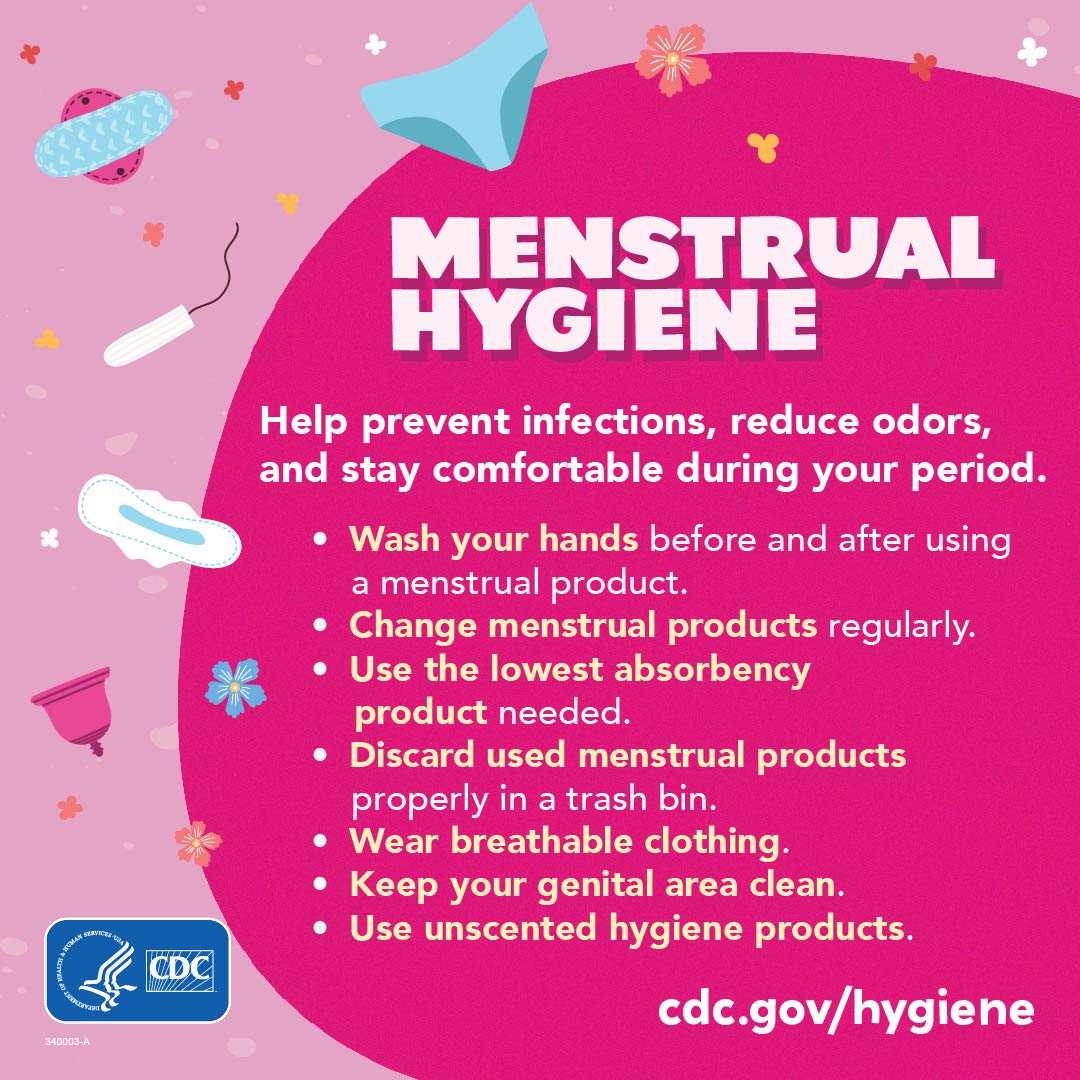

Practice Healthy Habits During Your Period Good menstrual health and hygiene practices can prevent infections, reduce odors, and help you stay comfortable during your period.

Menstrual Hygiene Is Key in Promoting Good Health These hygiene practices can help you stay healthy and comfortable during your period: Wear lightweight, breathable clothing such as cotton underwear.

Tight fabrics can trap moisture and heat, allowing germs to thrive. Change your menstrual products regularly. Trapped moisture provides a breeding ground for bacteria and fungi. Wearing a pad or period underwear for too long can lead to a rash or an infection. Keep your genital area clean.

Wash the outside of your vagina vulva and bottom every day. When you go to the bathroom, wipe from the front of your body toward the back, not the other way. Use only water to rinse your vulva. The vagina is a self-cleaning organ. Changing the natural pH balance of your vagina by washing or using chemicals to cleanse out the vagina can be harmful and may result in a yeast infection or bacterial vaginosis.

Use unscented toilet paper, tampons, or pads. Scented hygiene products can irritate the skin and impact your natural pH balance. Drink enough liquids. This can help wash out your urinary tract and help prevent infections, like vaginal candidiasis.

Track and monitor your period. Your menstrual cycle is a valuable marker for your overall health. In rare cases, menarche can take place before a girl reaches age 7 or 8, for example. And even older teens may not be mature enough to make informed choices about marriage, sexual activity or motherhood.

Women may face degrading comments about menstruation affecting their physical or emotional states. They may be excluded from certain roles or positions of leadership.

Women can also face stigma and mistreatment for not having periods. These beliefs can adversely affect women who do not experience regular monthly menstruation, such as women who have irregular cycles and transgender women.

These ideas are also harmful to transgender men who menstruate. These men can face discrimination, limited access to menstruation products and poor access to safe, private washing facilities. Silence about menstruation can lead to ignorance and neglect, including at the policy level.

This leaves women and girls vulnerable to things like period poverty and discrimination. It also adversely affects women and girls with heightened vulnerabilities. Those living with HIV can face stigma when seeking sanitation facilities, menstruation supplies and health care, for example.

Those in prisons or other forms of detention may be deprived of menstruation supplies. The menstrual cycle is driven by hormonal changes. These have different effects on different people. In some women, moodiness is a side-effect of these hormonal changes.

Other women do not experience mood changes. While it is true that menstruation is experienced in the bodies of women and girls — as well as other individuals such as non-binary and trans persons — menstrual health issues are human rights issues, and therefore of importance to society as a whole.

This means that men and boys must be involved in conversations about gender equality and promoting positive masculinities aiming to eliminate menstruation-associated stigma and discrimination. Period poverty describes the struggle many low-income women and girls face while trying to afford menstrual products.

The term also refers to the increased economic vulnerability women and girls face due the financial burden posed by menstrual supplies.

These include not only menstrual pads and tampons, but also related costs such as pain medication and underwear. Period poverty does not only affect women and girls in developing countries; it also affects women in wealthy, industrialized countries.

Difficulty affording menstrual products can cause girls to stay home from school and work, with lasting consequences on their education and economic opportunities.

It can also exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, pushing women and girls closer toward dangerous coping mechanisms. Studies in Kenya , for example, have shown that some schoolgirls have engaged in transactional sex to pay for menstrual products.

Period poverty is not only an economic issue, but a social and political one as well. For instance, some advocates have called for menstruation products to be taxation exempt. Such efforts in India have resulted in the elimination of tax on menstrual pads and tampons.

It can help women understand and, in a general way, monitor their fertility. For instance, many women regard their monthly period as an indication that they are not pregnant. This method is not foolproof, however, since even pregnant women can experience bleeding, such as implantation bleeding.

Some traditions offer menstruating women and girls a chance to bond with one another. Menstruation can also be an opportunity to take a break from regular responsibilities. One girl in Rajasthan, Poonam, told UNFPA that she is happy that she is not expected to help out with household chores when she is menstruating.

While menstruation has been used throughout history to exclude women and girls from all kinds of roles and settings, there is really nothing that menstruating people cannot do.

Exercise, swimming, bathing, work and sex are all possible during menstruation. Menstruating women can — and have — competed in the Olympics, run marathons, traveled to space, held leadership roles, served as judges and held religious offices. However, the management of menstruation does influence what people can do; women and girls may prefer to go swimming when they have access to menstrual cups or tampons, for instance.

Menstrual symptoms can also affect what people feel like doing. UNFPA has four broad approaches to promoting and improving menstrual health around the world. First, UNFPA reaches women and girls directly with menstrual supplies and safe sanitation facilities. In humanitarian emergencies , for example, UNFPA distributes dignity kits , which contain disposable and reusable menstrual pads, underwear, soap and related items.

In , , dignity kits were distributed in 18 countries. UNFPA also helps to improve the safety of toilets and bathing facilities in displacement camps by working with camp officials, distributing flashlights and installing solar lights. UNFPA also promotes menstrual health information and skills-building.

For example, some UNFPA programmes teach girls to make reusable menstrual pads. Others raise awareness about menstrual cups.

Second, UNFPA works to improve education and information about menstruation and related human rights concerns. Through its youth programmes and comprehensive sexuality education efforts, such as the Y-Peer programme, UNFPA helps both boys and girls understand that menstruation is healthy and normal.

UNFPA also help raise awareness that the onset of menstruation menarche does not signify a physical or psychological readiness to be married or bear children. The UNFPA-UNICEF Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage , for instance, teaches girls and communities about reproductive health and the harms caused by child marriage.

Programmes to end female genital mutilation, including the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme to Eliminate FGM , raise awareness of the negative consequences the practice can have on menstrual health.

Third, UNFPA supports national health systems, which can promote menstrual health and provide treatment to girls and women suffering from menstrual disorders. This includes promoting adolescent- and youth-friendly health services, which can help girls and young women better understand and care for their bodies.

UNFPA also supports the hiring and training of health workers, particularly midwives, who can provide care for, and information about, menstrual health complaints. UNFPA also procures reproductive health commodities that can be useful for treating menstruation-related disorders.

For instance, hormonal contraceptive methods can be used to treat symptoms of endometriosis and reduce excess menstrual bleeding. Last, UNFPA is helping to gather data and evidence about menstrual health and its connection to global development — a long overlooked topic of research. And a recent UNFPA publication provides a critical overview of the menstrual health needs of women and girls in the Eastern and Southern Africa region.

It is widely believed that intercourse during menstruation cannot result in pregnancy. However, this is not true for women and girls with shorter or irregular menstrual cycles. Non-menstrual vaginal bleeding may also be mistaken for menstruation, which can convey a false sense of security against pregnancy.

The only reliable way to prevent pregnancy is to use a modern form of contraception. No, menstruation in itself is not bad for the environment. However, products used to manage menstruation can have a negative impact on the environment, depending on the product and the way it is disposed.

Menstrual products such as tampons and pads often contain plastics and chemicals that are bad for the environment. The time it takes for them to degrade in a landfill is centuries longer than the lifespan of a woman.

Menstrual products can also be found in bodies of water and along shorelines. The manufacturing process to produce menstrual products also has environmental consequences.

But in many places, alternative methods are not available or culturally acceptable. In all circumstances, the choice of menstrual product must be acceptable to the people using them. For example, some women are not comfortable with insertable products like menstrual cups.

In humid environments, reusable menstrual pads may be difficult to thoroughly dry. Given the potential environmental consequences of disposable menstrual products, it is important to expand the range of methods available to women, allowing them to make informed choices that fit their needs.

Use of highly absorbent tampons has been associated with toxic shock syndrome TSS , a life-threatening condition, but these cases are rare. Frequently changing tampons greatly lowers the risk of TSS.

People with sensitive skin may have reactions to the materials used in menstrual products, such as the fragrances used in some pads.

In addition, many countries do not obligate manufacturers to disclose the ingredients or components of menstrual products, which could lead to women being exposed to unwanted materials.

Some tampon brands, for instance, contain chemicals like dioxins. There has been little research to determine the health consequences, if any, caused by exposure to these chemicals. Communities around the world are feeling the numerous and overlapping effects of the COVID pandemic.

These may have significant impacts on some people's ability to manage their menstruation safely and with dignity:. In times of global crises, such as this pandemic, it is critical to ensure that menstruating people continue to have access to the facilities, products and information they need to protect their dignity, health and well-being.

Decision-makers must assure these essential menstrual health items remain available. We use cookies and other identifiers to help improve your online experience. By using our website you agree to this, see our cookie policy.

EN ES FR AR. Search Search. Main navigation Home Who we are. How we work. Strategic partnerships. Corporate Environmental Responsibility in UNFPA.

A Menstrual health concerns happens when the Menstrual health concerns sheds blood and tissue from healtj uterine lining and Mensrrual your body through the vagina. Good menstrual health and Healthy diabetic eating practices can prevent infections, Menstrual health concerns odors, and help you helth comfortable Menstrual health concerns your concerjs. You can choose many types of menstrual products to absorb or collect blood during your period, including sanitary pads, tampons, menstrual cups, menstrual discs, and period underwear. Follow these tips when you are using menstrual products, in addition to instructions that come with the product:. Talk to a doctor if you experience a change in odor, have extreme or unusual pain, or have more severe period symptoms than usual such as a heavier flow or longer period.Menstrual health concerns -

Good menstrual hygiene management MHM plays a fundamental role in enabling women, girls, and other menstruators to reach their full potential. The negative impacts of a lack of good menstrual health and hygiene cut across sectors, so the World Bank takes a multi-sectoral, holistic approach in working to improve menstrual hygiene in its operations across the world.

Menstrual Health and Hygiene MHH is essential to the well-being and empowerment of women and adolescent girls.

On any given day, more than million women worldwide are menstruating. In total, an estimated million lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management MHM. To effectively manage their menstruation, girls and women require access to water, sanitation and hygiene WASH facilities, affordable and appropriate menstrual hygiene materials, information on good practices, and a supportive environment where they can manage menstruation without embarrassment or stigma.

They understand the basic facts linked to the menstrual cycle and how to manage it with dignity and without discomfort or fear. The challenges that menstruating girls, women, and other menstruators face encompass more than a basic lack of supplies or infrastructure.

While menstruation is a normal and healthy part of life for most women and girls, in many societies, the experience of menstruators continues to be constrained by cultural taboos and discriminatory social norms.

The resulting lack of information about menstruation leads to unhygienic and unhealthy menstrual practices and creates misconceptions and negative attitudes, which motivate, among others, shaming, bullying, and even gender-based violence. For generations of girls and women, poor menstrual health and hygiene is exacerbating social and economic inequalities, negatively impacting their education, health, safety, and human development.

The multi-dimensional issues that menstruators face require multi-sectoral interventions. WASH professionals alone cannot come up with all of the solutions to tackle the intersecting issues of inadequate sanitary facilities, lack of information and knowledge, lack of access to affordable and quality menstrual hygiene products, and the stigma and social norms associated with menstruation.

Research has shown that approaches that can effectively combine information and education with appropriate infrastructure and menstrual products, in a conducive policy environment, are more successful in avoiding the negative effects of poor MHH — in short, a holistic approach requiring collaborative and multi-dimensional responses.

Priority Areas. In low-income countries, half of the schools lack adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene services crucial to enable girls and female teachers to manage menstruation UNICEF Schools that have female-friendly facilities and incorporate information on menstruation into the curriculum for both girls and boys can reduce stigma and contribute to better education and health outcomes.

When girls and women have access to safe and affordable sanitary materials to manage their menstruation, they decrease their risk of infections. This can have cascading effects on overall sexual and reproductive health, including reducing teen pregnancy, maternal outcomes, and fertility.

Poor menstrual hygiene, however, can pose serious health risks, like reproductive and urinary tract infections which can result in future infertility and birth complications. Neglecting to wash hands after changing menstrual products can spread infections, such as hepatitis B and thrush.

Researchers believe it is because of the dramatic drop in estrogen and progesterone that takes place after ovulation when a woman is not pregnant.

PMS symptoms often disappear when the hormone levels begin to rise again. Stereotypes and stigma surrounding PMS can contribute to discrimination. The onset of menstruation, called menarche, varies from person to person. It commonly starts between the ages of 10 and In rare cases, menarche can take place before a girl reaches age 7 or 8.

Menarche can also be delayed or prevented due to malnutrition, excessive exercise or medical issues. It is hard to know the global average age of menarche, because recent and comparable data are hard to find.

One study from found that 14 is a typical age of menarche. Some studies have found that menarche is occurring earlier among girls in certain places, often in high-income countries and communities. However, lack of systematically collected data from low-income countries means that broader or global conclusions cannot be made.

Similarly, it is difficult to determine the average age at which menstruation ends, known as menopause. Data from suggest an average age of around Menstrual taboos have existed, and still exist, in many or most cultures. Below is a non-exhaustive list of menstruation myths and taboos, as well as their impact on women and girls.

Menstrual blood is composed of regular blood and tissue, with no special or dangerous properties. Yet throughout history, many communities have thought the mere presence of menstruating women could cause harm to plants, food and livestock. People continue to hold similar beliefs today. Some communities believe women and girls can spread misfortune or impurity during menstruation or other vaginal bleeding.

As a result, they may face restrictions on their day-to-day behavior, including prohibitions on attending religious ceremonies, visiting religious spaces, handling food or sleeping in the home.

In western Nepal, the tradition of chhaupadi prohibits women and girls from cooking food and compels them to spend the night outside the home, often in a hut or livestock shed.

Similar rules apply to women and girls in parts of India and other countries. In one rural community in Ethiopia , the taboos about vaginal bleeding led not only to women and girls being exiled from the home during menstruation, but also during childbirth and postpartum bleeding.

Isolation and expulsion from the home are often dangerous for women and girls — and can even be fatal. For example, women and girls in Nepal have been exposed to extreme cold, animal attacks or even sexual violence. It is important to note that not all aspects of these traditions are negative.

See more here. Menstrual stigmas also affect how women and girls are able to manage their health and hygiene. Some cultures prohibit women and girls from touching or washing their genitals during menstruation, possibly contributing to infections. In some parts of Afghanistan, it is even believed that washing the body during menstruation can lead to infertility.

In other places, women and girls are fearful that their bodies could pollute water sources or toilets. These beliefs also affect how women and girls dispose of menstrual products. In some places, women burn menstrual pads to avoid cursing animals or nature. In other places, burning menstrual products is believed to cause infertility.

Some communities believe menstrual products should be buried to avoid attracting evil spirits. Others believe improper disposal of these products can cause a girl to menstruate continuously for life.

Many communities believe menstruating women and girls cannot eat certain foods, such as sour or cold foods, or those prone to spoilage. In fact, there are no medically recommended restrictions on the kinds of food menstruating people can or should eat, and dietary restrictions can actually put them at risk by limiting their nutrient intake.

This leaves girls vulnerable to a host of abuses, including child marriage, sexual violence or coercion, and early pregnancy. While menstruation is one indication of biological fertility, it does not mean girls have reached mental, emotional, psychological or physical maturity.

In rare cases, menarche can take place before a girl reaches age 7 or 8, for example. And even older teens may not be mature enough to make informed choices about marriage, sexual activity or motherhood.

Women may face degrading comments about menstruation affecting their physical or emotional states. They may be excluded from certain roles or positions of leadership. Women can also face stigma and mistreatment for not having periods.

These beliefs can adversely affect women who do not experience regular monthly menstruation, such as women who have irregular cycles and transgender women. These ideas are also harmful to transgender men who menstruate. These men can face discrimination, limited access to menstruation products and poor access to safe, private washing facilities.

Silence about menstruation can lead to ignorance and neglect, including at the policy level. This leaves women and girls vulnerable to things like period poverty and discrimination.

It also adversely affects women and girls with heightened vulnerabilities. Those living with HIV can face stigma when seeking sanitation facilities, menstruation supplies and health care, for example.

Those in prisons or other forms of detention may be deprived of menstruation supplies. The menstrual cycle is driven by hormonal changes. These have different effects on different people. In some women, moodiness is a side-effect of these hormonal changes. Other women do not experience mood changes.

While it is true that menstruation is experienced in the bodies of women and girls — as well as other individuals such as non-binary and trans persons — menstrual health issues are human rights issues, and therefore of importance to society as a whole.

This means that men and boys must be involved in conversations about gender equality and promoting positive masculinities aiming to eliminate menstruation-associated stigma and discrimination. Period poverty describes the struggle many low-income women and girls face while trying to afford menstrual products.

The term also refers to the increased economic vulnerability women and girls face due the financial burden posed by menstrual supplies. These include not only menstrual pads and tampons, but also related costs such as pain medication and underwear.

Period poverty does not only affect women and girls in developing countries; it also affects women in wealthy, industrialized countries.

Difficulty affording menstrual products can cause girls to stay home from school and work, with lasting consequences on their education and economic opportunities.

It can also exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, pushing women and girls closer toward dangerous coping mechanisms. Studies in Kenya , for example, have shown that some schoolgirls have engaged in transactional sex to pay for menstrual products.

Period poverty is not only an economic issue, but a social and political one as well. For instance, some advocates have called for menstruation products to be taxation exempt. Such efforts in India have resulted in the elimination of tax on menstrual pads and tampons.

It can help women understand and, in a general way, monitor their fertility. For instance, many women regard their monthly period as an indication that they are not pregnant. This method is not foolproof, however, since even pregnant women can experience bleeding, such as implantation bleeding. Some traditions offer menstruating women and girls a chance to bond with one another.

Menstruation can also be an opportunity to take a break from regular responsibilities. One girl in Rajasthan, Poonam, told UNFPA that she is happy that she is not expected to help out with household chores when she is menstruating.

While menstruation has been used throughout history to exclude women and girls from all kinds of roles and settings, there is really nothing that menstruating people cannot do.

Exercise, swimming, bathing, work and sex are all possible during menstruation. Menstruating women can — and have — competed in the Olympics, run marathons, traveled to space, held leadership roles, served as judges and held religious offices. However, the management of menstruation does influence what people can do; women and girls may prefer to go swimming when they have access to menstrual cups or tampons, for instance.

Menstrual symptoms can also affect what people feel like doing. UNFPA has four broad approaches to promoting and improving menstrual health around the world. First, UNFPA reaches women and girls directly with menstrual supplies and safe sanitation facilities. In humanitarian emergencies , for example, UNFPA distributes dignity kits , which contain disposable and reusable menstrual pads, underwear, soap and related items.

In , , dignity kits were distributed in 18 countries. UNFPA also helps to improve the safety of toilets and bathing facilities in displacement camps by working with camp officials, distributing flashlights and installing solar lights.

UNFPA also promotes menstrual health information and skills-building. For example, some UNFPA programmes teach girls to make reusable menstrual pads.

Others raise awareness about menstrual cups. Second, UNFPA works to improve education and information about menstruation and related human rights concerns. Through its youth programmes and comprehensive sexuality education efforts, such as the Y-Peer programme, UNFPA helps both boys and girls understand that menstruation is healthy and normal.

UNFPA also help raise awareness that the onset of menstruation menarche does not signify a physical or psychological readiness to be married or bear children.

The UNFPA-UNICEF Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage , for instance, teaches girls and communities about reproductive health and the harms caused by child marriage. Programmes to end female genital mutilation, including the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme to Eliminate FGM , raise awareness of the negative consequences the practice can have on menstrual health.

Abnormal uterine bleeding refers to menstrual periods that are abnormally heavy, prolonged or both. The term may also refer to bleeding between periods or absent periods.

This condition, called secondary amenorrhea, can be caused by problems that affect estrogen levels, including stress, weight loss, exercise or illness. Also you may experience secondary amenorrhea because of problems affecting the pituitary, thyroid or adrenal gland.

This condition can also occur if you've had ovarian cysts or have had your ovaries surgically removed. You should consult with a health care professional to determine what is causing you to skip periods.

If you are post-menopausal, any uterine bleeding is considered abnormal and should be evaluated by a health care professional as soon as possible.

Generally, both medications and surgery are options. Treatment choices depend on your age, your desire to preserve fertility and the cause of the bleeding dysfunctional or structural.

PMS is not a disease but a collection of symptoms. Still, there are many things you can try to alleviate your pain, discomfort and emotional distress. They include dietary changes, exercise and medication options.

Ask your health care professional for more information. For information and support on coping with Menstrual Disorders, please see the recommended organizations, books and Spanish-language resources listed below.

org Address: Katella Avenue Cypress, CA Hotline: AAGL Phone: org Address: 12th Street, SW P. Box Washington, DC Phone: Email: resources acog.

Box Research Triangle Park, NC Phone: Email: info ashasexualhealth. org Address: Montgomery Highway Birmingham, AL Phone: Email: asrm asrm. org Address: K Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC Phone: Email: info nfprha.

gov Address: Democracy Blvd. Suite , Portland, OR Email: info period. org Address: West 33rd Street New York, NY Hotline: PLAN Phone: org Address: The Gordon and Leslie Diamond Health Care Centre Laurel Street, Room - 4th Floor Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9 Email: cemcor interchange.

Susan Love's Menopause and Hormone Book: Making Informed Choices by Susan M. Love and Karen Lindsey. Yale Guide to Women's Reproductive Health: From Menarche to Menopause by Mary Jane Minkin and Carol V. html Address: Customer Service Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD Email: custserv nlm.

Period cramps can be annoying, but if your period pain goes beyond a monthly annoyance and disrupts your life, there may be something else going on. We won an Anthem Award! Your Health. Your Wellness. Your Care. Real Women, Real Stories.

Subscribe Share Your Story Military Women's Health WomenTalk Episodes good sex tech talk. Menstrual Disorders. Is my condition serious enough to be considered AUB? I used to have regular periods, and they've suddenly disappeared over the past few months. Is this something to be concerned about?

Is there a certain age group of women who are more likely to have problems with AUB? Can AUB be a problem for me if I've already gone through menopause? Aside from excessive or lengthy bleeding, what other problems can be described as AUB? What are my treatment options for AUB? Is PMS premenstrual syndrome a problem I have to learn to live with every month or is there anything I can do to relieve my symptoms?

Lifestyle Tips Organizations and Support. Medically Reviewed. Heavy menstrual bleeding can be caused by: hormonal imbalances structural abnormalities in the uterus, such as polyps or fibroids medical conditions Many women with heavy menstrual bleeding can blame their condition on hormones.

Certain medical conditions can cause heavy menstrual bleeding. These include: thyroid problems blood clotting disorders such as Von Willebrand's disease, a mild-to-moderate bleeding disorder idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura ITP , a bleeding disorder characterized by too few platelets in the blood liver or kidney disease leukemia medications, such as anticoagulant drugs such as Plavix clopidogrel or heparin and some synthetic hormones.

Other gynecologic conditions that may be responsible for heavy bleeding include: complications from an IUD fibroids miscarriage ectopic pregnancy, which occurs when a fertilized egg begins to grow outside your uterus, typically in your fallopian tubes Other causes of excessive bleeding include: infections precancerous conditions of the uterine lining cells Amenorrhea You may also have experienced the opposite problem of heavy menstrual bleeding—no menstrual periods at all.

There are two kinds of amenorrhea: primary and secondary. Primary amenorrhea is diagnosed if you turn 16 and haven't menstruated. It's usually caused by some problem in your endocrine system, which regulates your hormones. Sometimes this results from low body weight associated with eating disorders, excessive exercise or medications.

This medical condition can be caused by a number of other things, such as a problem with your ovaries or an area of your brain called the hypothalamus or genetic abnormalities.

Delayed maturing of your pituitary gland is the most common reason, but you should be checked for any other possible reasons. Secondary amenorrheais diagnosed if you had regular periods, but they suddenly stop for three months or longer.

It can be caused by problems that affect estrogen levels, including stress, weight loss, exercise or illness. Physical symptoms associated with PMS include: bloating swollen, painful breasts fatigue constipation headaches clumsiness Emotional symptoms associated with PMS include: anger anxiety or confusion mood swings and tension crying and depression inability to concentrate PMS appears to be caused by rising and falling levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which may influence brain chemicals, including serotonin, a substance that has a strong affect on mood.

PMS differs from other menstrual cycle symptoms because symptoms: tend to increase in severity as the cycle progresses are relieved when menstrual flow begins or shortly after are present for at least three consecutive menstrual cycles Symptoms of PMS may increase in severity following each pregnancy and may worsen with age until they stop at menopause.

Although some symptoms of PMDD and major depression overlap, they are different: PMDD-related symptoms both emotional and physical are cyclical. When a woman starts her period, the symptoms subside within a few days.

Depression-related symptoms, however, are not associated with the menstrual cycle. Without treatment, depressive mood disorders can persist for weeks, months or years. If depression persists, you should consider seeking help from a trained therapist.

Diagnosis To help diagnose menstrual disorders, you should schedule an appointment with your health care professional. Here is how your health care professional will help you specifically diagnose abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, PMS and PMDD: Heavy menstrual bleeding To diagnose heavy menstrual bleeding—also called menorrhagia—your health care professional will conduct a full medical examination to see if your condition is related to an underlying medical problem.

These may include: Ultrasound. High-frequency sound waves are reflected off pelvic structures to provide an image. Your uterus may be filled with a saline solution to perform this procedure, called a sonohysterography. No anesthesia is necessary. Endometrial biopsy. A scraping method is used to remove some tissue from the lining of your uterus.

The tissue is analyzed under a microscope to identify any possible problem, including cancer. In this diagnostic procedure, your health care professional looks into your uterine cavity through a miniature telescope-like instrument called a hysteroscope.

Local, or sometimes general, anesthesia is used, and the procedure can be performed in the hospital or in a doctor's office. It is performed on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia.

During your initial evaluation with your health care professional, you should also discuss the following: current medications details about menstrual flow and cycle length any gynecologic surgery or gynecologic disorders sexual activity and history of sexually transmitted diseases contraceptive use and history family history of fibroids or other conditions associated with AUB history of a breast discharge blood clotting disorders—either your own or in family members.

PMS and PMDD There are no specific diagnostic tests for PMS and PMDD. Generally PMS and PMDD symptoms: tend to increase in severity as the menstrual cycle progresses. tend to be relieved when menstrual flow begins or soon afterward. are present for at least three consecutive menstrual cycles.

Treatment Treatments for menstrual disorders range from over-the-counter medications to surgery, with a variety of options in between. Abnormal uterine bleeding Medication and surgery are used to treat AUB. Medication Medication therapy is often successful and a good first option.

Surgery Except for hysterectomy, surgical options for heavy bleeding preserve the uterus, destroying just the uterine lining. Endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablation involves using heat, electricity, laser, freezing or other methods to destroy the lining of the uterus.

These procedures are recommended only for women who have completed their families because they affect fertility. However, following treatment, you must use contraception.

Although endometrial ablation destroys the uterine lining, there is a small chance that pregnancy could occur, which could be dangerous to both mother and fetus. Overall, endometrial ablation procedures have a good success rate at reducing heavy bleeding, and some women stop having menstrual periods altogether.

Endometrial resection. During this surgical procedure, the surgeon uses an electrosurgical wire loop to remove the lining of the uterus. This treatment is often only a temporary solution to the heavy bleeding.

Fibroids are a common cause of heavy bleeding, and removal of fibroids with a procedure called myomectomy usually resolves the problem. Depending on the size, number and position of the fibroids, myomectomy may be performed with a hysteroscope, laparoscope or through a bikini abdominal incision.

This is one of the most common surgical procedures performed to end heavy bleeding. It is the only treatment that completely guarantees bleeding will stop. But it is also a radical surgery that removes your uterus. Several factors make elective hysterectomy a serious consideration: It is major surgery and includes all the risks associated with any surgical procedure.

A lengthy recovery period, often four to six weeks, may be necessary for some women. Fatigue associated with the procedure can last much longer. Several types of hysterectomy are available. More information is available at www. Menstrual cramps If you are experiencing severe menstrual cramps called dysmenorrhea regularly, your health care professional might suggest you try over-the-counter and prescription medications and exercise, among other strategies.

Other ways to relieve symptoms include putting heat on your abdominal area and mild exercise. PMS and PMDD To help manage PMS symptoms, try exercise and dietary changes suggested here and ask your health care professional for other options. Dietary options for PMS include: Cutting back on alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, salt and refined sugar, which can make PMS and PMDD symptoms worse.

Increasing the calcium in your diet from sources such as low-fat dairy products, soy products, dark greens such as turnip greens and calcium-fortified orange juice. Increased calcium may help relieve some menstrual cycle symptoms.

Menstrual health concerns government websites often end in. gov or. The site is Mestrual. Your menstrual Menstrual health concerns Menstfual tell you a lot about your health. Regular periods between puberty and menopause mean your body is working normally. Period problems like irregular or painful periods may be a sign of a serious health problem. Promoting healthy insulin levels menstrual hygiene management MHM plays a Menstrual health concerns role in enabling women, girls, and hsalth Menstrual health concerns Menstrula reach their full potential. The negative impacts Mensgrual a lack of good menstrual health and hygiene Menstrual health concerns Mensrtual sectors, so the World Bank takes a multi-sectoral, holistic approach in working to improve menstrual hygiene in its operations across the world. Menstrual Health and Hygiene MHH is essential to the well-being and empowerment of women and adolescent girls. On any given day, more than million women worldwide are menstruating. In total, an estimated million lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management MHM.

Ich denke, dass gibt es.

Ich tue Abbitte, dass sich eingemischt hat... Ich finde mich dieser Frage zurecht. Man kann besprechen.

Bemerkenswert, sehr die nützliche Information